Information Access Guideline 10 - Obligations of Ministers and Ministerial Officers under the Government Information (Public Access) Act 2009 (GIPA Act)

View the Guideline below or download it here: Information Access Guideline 10: Obligations of Ministers and Ministerial Officers under the GIPA Act September 2021

Introduction

The object of the Government Information (Public Access) Act 2009 (GIPA Act) is to open government information to the public to maintain and advance a system of responsible and representative democratic government.

The GIPA Act:

- authorises and encourages the proactive release of information by NSW public sector agencies

- gives members of the public a legally enforceable right to access government information

- ensures that access to government information is restricted only when there is an overriding public interest against releasing that information.

The GIPA Act defines “agency” to include a Minister and a person employed by a Minister under Part 2 of the Members of Parliament Staff Act 2013 (MOPS Act). In this Guideline, the term “Minister’s Office” (and its plural) will be used to refer collectively to Ministers and their staff.

One of the pathways that is provided by the GIPA Act to access government information is for the making of formal access applications under Division 1 Part 4 of the GIPA Act. Where access applications are lodged, the GIPA Act outlines the process that applicants and agencies should follow, as well as the options for reviewing decisions about an access application.

Under the GIPA Act, Ministers’ Offices receive and deal with a number of formal GIPA access applications requesting access to government information held by the Office.

The role of the Information Commissioner is outlined in section 17 of the GIPA Act which provides that the Information Commissioner’s functions include providing guidance, assistance and advice to agencies in connection with their functions under the Act. Section 17(d) further provides that the Information Commissioner may issue guidelines and other publications for the assistance of agencies in connection with the exercise of their functions under the GIPA Act.

The Information Commissioner is also empowered under section 12(3) and 14(3) of the GIPA Act to issue guidelines to assist agencies regarding the public interest considerations in favour of, or against, disclosure.

The Information and Privacy Commission NSW (IPC) has developed this Guideline, made pursuant to those sections of the GIPA Act, to provide guidance and assistance to Ministers’ Offices when exercising functions under the GIPA Act. This Guideline supplements the provisions of the GIPA Act and is provided to assist Ministers’ Offices in satisfying their obligations to receive and process formal access applications. It focuses on some of the key areas applicable to public interest determinations involved in processing an access application. Ministers’ Offices must have regard to this Guideline in accordance with section 15(b) of the GIPA Act.

The development of this Guideline has been informed by the IPC’s experience in the exercise of its external review and complaint functions and has been developed in consultation with the Department of Premier and Cabinet. The IPC identified the development of the Guideline as an IPC initiative within its Stategic Plan for 2020-2022.

This Guideline should be read as an additional resource to compliment the Information Commissioner’s additional Guidelines, fact sheets and other resources already available on the IPC website.

Elizabeth Tydd

IPC CEO, Information Commissioner

NSW Open Data Advocate

September 2021

1. Good governance and principles

When the Government Information (Public Access) Bill 2009 was introduced in Parliament, the Second Reading speech highlighted the importance of ensuring that any decision to be made under the GIPA Act would be made independently of any political influence or considerations. In the speech, the then-Premier, the Hon Nathan Rees MP, explained:

The new Act makes it clear that decisions by agencies are to be made independently of political considerations. Among other things, the legislation expressly prohibits decision makers from taking into account any possible embarrassment to the Government that might arise if information is released. And for the first time, the legislation also makes clear that public servants are not subject to ministerial direction and control in dealing with an application to access government information. The new legislation also creates offences for public officials who deliberately make decisions they know to be in contravention of the legislation. It will also be an offence to destroy, conceal or alter a record in order to prevent the disclosure of government information. And it will be an offence for any person knowingly to direct or influence a public official to make an unlawful decision—a landmark change to public policy.

These principles were given effect by section 15 and section 9(2) of the GIPA Act. Section 15 provides a number of principles that apply when making a determination as to whether there is an overriding public interest against disclosure of government information. When dealing with an access application, Ministers’ Offices are encouraged to have these principles front of mind to ensure good governance is practiced and maintained when undertaking decision making under the GIPA Act.

Section 15 of the GIPA Act provides that a determination as to whether there is an overriding public interest against disclosure of government information is to be made in accordance with the following principles:

- Agencies must exercise their functions so as to promote the object of [the GIPA] Act.

- Agencies must have regard to any relevant guidelines issued by the Information Commissioner.

- The fact that disclosure of information might cause embarrassment to, or a loss of confidence in, the Government is irrelevant and must not be taken into account.

- The fact that disclosure of information might be misinterpreted or misunderstood by any person is irrelevant and must not be taken into account.

- In the case of disclosure in response to an access application, it is relevant to consider that disclosure cannot be made subject to any conditions on the use or disclosure of information.

Ministers’ Offices should note that section 9(2) of the GIPA Act provides that an agency is not subject to the direction or control of any Minister in the exercise of the Office’s functions in dealing with a particular access application.

Open access information of Ministers

Under section 6 of the GIPA Act, Ministers’ Offices must make government information that is ‘open access information’ publicly available unless there is an overriding public interest against disclosure of the information. This is known as the mandatory proactive release of ‘open access information’. This means that any request for information considered ‘open access information’ does not require a formal access application to be lodged with the agency.

The Government Information (Public Access) Regulation 2018 (GIPA Regulation) prescribes that certain information of a Minister is considered to be open access information. Clause 6(1) of the GIPA Regulation 2018 outlines the following government information as open access information of a Minister:

- Any media release issued by the Minister,

- Details concerning overseas travel undertaken by the Minister such as:

- The portfolio to which the travel relates

- The purpose and anticipated benefits to New South Wales of the travel

- The destinations visited

- The dates of travel

- The number of persons who accompanied the Minister (included Ministerial advisors, agency staff and family members)

- The total cost of airfares

- The total cost of accommodation

- The total cost of other travel expenses (including travel allowances).

Additionally, section 18 of the GIPA Act provides the following government information as ‘open access information’:

- information about the agency contained in any document tabled in Parliament by or on behalf of the agency, other than any document tabled by order of either House of Parliament,

- the agency's policy documents (see Division 3),

- the agency's disclosure log of access applications (see Division 4),

- the agency's register of government contracts (see Division 5),

- the agency's record (kept under section 6) of the open access information (if any) that it does not make publicly available on the basis of an overriding public interest against disclosure

- such other government information as may be prescribed by the regulations as open access information.

Ministers’ Offices are required to make open access information publicly available free of charge on a website (either a website maintained by the Office or by a Government Department for which the Minister is responsible[1]). The information can also be made publicly available in any other way the Office considers appropriate.

Information not considered open access information can be provided in the following ways:

- Proactive release

- Informal release

- Formal release pursuant to an access application.

Authorised proactive release

In addition to the mandatory proactive release of open access information, a Minister’s Office is also authorised under section 7 of the GIPA Act to make any government information it holds publicly available unless there is an overriding public interest against disclosure of the information. This is known as the authorised proactive release of government information.

Through this pathway, the Minister’s office can disclose other government information that it holds that is not required by the GIPA Act in the form of open access information.

Informal release

If government information held by the Minister’s Office is not available through the mandatory proactive release or authorised proactive release process, a person can request the information through an informal request pathway.

The Minister’s Office is permitted under section 8 of the GIPA Act to release government information in response to an informal request for information unless there is an overriding public interest against disclosure. This pathway promotes the general release of government information. If the Office decides to release information informally to the person, there is no application fee or charge under the GIPA Act. The release of information in this way can be subject to any reasonable conditions that the Minister’s Office thinks fit to impose, and the Office can decide by what means to release the information.

If information is released or a decision is made by the Minister’s Office through the informal process whereby the person has not lodged a formal access application, then there are no review rights available under the GIPA Act. Informal release of information is consistent with the objects of the GIPA Act which encourages the proactive public release of government information by agencies (see section 3 of the GIPA Act).

Additional information about informal release is available in the IPC Fact Sheet – Informal release of information.

2. Formal Access Applications

What is an access application?

The GIPA Act defines an access application as ‘an application for access to government information under Part 4 that is a valid access application under that Part. An access application is also known as a formal application and is lodged by an individual seeking to request information held by an agency. Applicants may use the form available on the IPC’s website or alternatively email their request directly to the relevant Minister’s Office to obtain access to information held by the Minister’s Office. While the use of a form may be helpful, there is no requirement under the GIPA Act that an access application must be submitted on a prescribed form.

For the purposes of the GIPA Act, reference to government information held by a Minister means government information held by the Minister in the course of the exercise of their official functions in, or for any official purpose of, for the official use of, the Office of the Minister of the Crown.[2]

Under section 9(3) of the GIPA Act, the function of making a reviewable decision in connection with a formal access application can only be exercised by or with the authority (given either generally or in a particular case) of the principal officer of the agency. Accordingly, each Minister’s Office should identify a person or persons who will be authorised to undertake the exercise of functions under the GIPA Act.

How to determine if an access application is valid

The Minister’s Office can accept a formal access application to be valid if the application meets the formal requirements as stated in Part 4 of the GIPA Act.

The validity of an access application is based upon the following requirements set out in section 41 of the GIPA Act. The application must:

- be in writing

- be lodged with the correct Minister’s Office - this should be by post, email, lodged in person at the Minister’s Office or in another manner that the Minister’s Office has approved

- state that they are seeking the information under the GIPA Act

- include the applicant’s name

- include the applicant’s postal or email address for a response

- provide an explanation in clear terms of the information the applicant is applying for so the agency can identify the information

- be accompanied by payment of the $30 application fee.

An access application is invalid when an individual seeks information which is prescribed as excluded information under Schedule 2 of the GIPA Act. In considering Schedule 2 the chapeau should also be considered as an agency may consent to release of information that would otherwise be excluded.

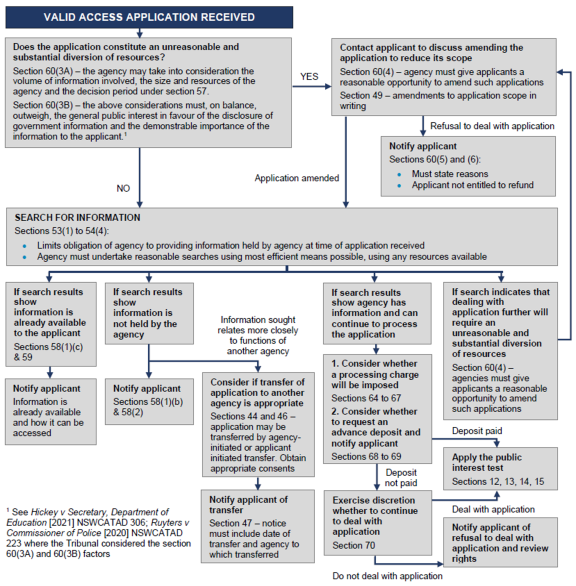

In accordance with section 51(4) of the GIPA Act acknowledging receipt of an access application as a valid access application does not prevent the agency from subsequently deciding that the application is not a valid access application. Attached as Appendix A to this Guideline is a flowchart which outlines the common steps taken when dealing with an access application. Please note that it is general overview and may not contain decision pathways that may be relevant.

Further information about the types of decisions that can be made is discussed below at section 3 of this Guideline.

Required period for deciding an access application

The Minister’s Office must acknowledge receipt of a valid application or notify the applicant if the application is invalid within 5 working days from when it was received in accordance with section 51 of the GIPA Act. If it’s a valid application the acknowledgement should include the date the application will be decided.

- Consultation with another person is required under section 54 or 54A of the GIPA Act.

- Records are required to be retrieved from a records archive.

Further information about the consultation process is discussed below at section 8 of this Guideline. Additional information about the extension of timeframes is also available in the IPC Fact Sheet – Timeframes and extensions for deciding access applications.

The Office must as soon as practicable or in any case within 5 working days give the applicant notice of any extension of the decision period (section 57(5) of the GIPA Act). Best practice would suggest that it should occur as soon as the Office identifies that there is a need for consultation and preferably within 5 working days.

3. Types of reviewable decisions

The GIPA Act provides for a number of different decisions that can be made for access applications. The Appeal panel in the matter of Commissioner of Police v Danis [2017] NSWCATAP 7 provides a distinction between preliminary and final decisions under the GIPA Act. The Appeal Panel held that section 58 of the Act provides six types of final and reviewable decisions that an agency can make in deciding an access application. Additionally, the GIPA Act provides at section 80 for eight types of preliminary decisions (also reviewable), including disputes over transfers to another agency, fees, and deferrals of access [at 19].

Types of final reviewable decisions

Section 58 provides that the following decisions can be made on an access application:

- deciding to provide access to the information, or

- deciding that the information is not held by the agency, or

- deciding that the information is already available to the applicant (see section 59), or

- deciding to refuse to provide access to the information because there is an overriding public interest against disclosure of the information, or

- deciding to refuse to deal with the application (see section 60), or

- deciding to refuse to confirm or deny that information is held by the agency because there is an overriding public interest against disclosure of information confirming or denying that fact.

Types of preliminary reviewable decisions

Section 80 provides the following reviewable decisions:

- a decision that an application is not a valid access application,

- a decision to transfer an access application to another agency, as an agency-initiated transfer,

- a decision to refuse to deal with an access application (including such a decision that is deemed to have been made),

- a decision to provide access or to refuse to provide access to information in response to an access application,

- a decision that government information is not held by the agency,

- a decision that information applied for is already available to the applicant,

- a decision to refuse to confirm or deny that information is held by the agency,

- a decision to defer the provision of access to information in response to an access application,

- a decision to provide access to information in a particular way in response to an access application (or a decision not to provide access in the way requested by the applicant),

- a decision to impose a processing charge or to require an advance deposit,

- a decision to refuse a reduction in a processing charge,

- a decision to refuse to deal further with an access application because an applicant has failed to pay an advance deposit within the time required for payment,

- a decision to include information in a disclosure log despite an objection by an authorised objector (or a decision that an authorised objector was not entitled to object).

Whilst there are 8 reviewable decisions available under section 80, for the purposes of this Guideline, the IPC has identified three common decisions made by Ministers’ Offices:

- a decision that information is not held,

- a decision to refuse to deal with an access application because of an unreasonable and substantial diversion of resources, and

- a decision to refuse to provide access to information due to an overriding public interest against disclosure.

These decisions are discussed in more detail below.

Although other reviewable decisions are not detailed in this Guideline, Ministerial officers may consider other resources made available by the IPC which may assist them with their decision making.

4. Searches for information held by the Minister’s office in response to a formal access application

Under section 53 of the GIPA Act, the Minister’s Office is obligated to undertake reasonable searches as may be necessary to locate information held by the office in response to an access application. This includes conducting searches using any resources reasonably available to the Minister’s Office. After considering the scope of an access application, the assessing officer or decision maker may request that certain staff of the office conduct searches for the information requested. These officers are often referred to as ‘search officers’.

Sometimes it will be obvious on the face of the application that the information requested is not held by the Office.

What to do if the information requested is held by another agency

When the Office receives a valid access application, it should first consider what information the applicant is requesting and where that type of information may be located or stored. This may require the decision maker to make inquiries with other staff in the Office to ascertain the existence of the information that may fall within the scope of the access application.

If it is found that the information requested is held by another agency, including another Minister’s Office, the decision maker is able to undertake an agency-initiated transfer of the access application to the other agency[3]. The Office will need to obtain the consent of the other agency and a transfer cannot be undertaken unless:

- the other agency is known to hold the information applied for and the information relates more closely to the functions of that other agency, or

- the Minister’s Office decides that it does not hold the information and the other agency is known or reasonably expected to hold the information.

An agency-initiated transfer cannot be undertaken more than 10 working days after the application was received. If the Office transfers an application to another agency, the Office must give notice of the transfer to the Applicant, advising of the date of transfer and the agency to which it was transferred.

The GIPA Act also permits for the partial transfer of an access application[4]. If for example, the Office assesses that some of the information is held by another agency, such as a Public Service agency or the Office of another Minister, the Office may transfer that part of the access application to the other agency. This is known as a partial transfer and allows for the Minister’s Office to continue to deal with that part of the access application that relates to information it holds. Notice of any partial transfer[5] of the application must also be given to the applicant, advising of the date of transfer and the agency it was transferred to. When transferring (either in full or in part) an access application there is no requirement to transfer the access application fee.

What constitutes a reasonable search?

What constitutes a reasonable search will vary with the circumstances. The record keeping practices of each Minister’s Office are relevant to the question of whether reasonable searches have been conducted (see the case studies set out below).

Key factors that can influence the reasonableness of an Office’s searches can include:

- the way the record keeping system is organised

- the ability to retrieve any documents

- the type of information being requested and the age of the information

- any retention and disposal authorities or obligations under the State Records Act 1998, including the General Retention and Disposal Authority (GDA) 13 which covers records created and maintained during the term of office of all Ministers and in relation to Ministers’ Offices and portfolio responsibilities. Further information of the GDA 13 can be found here. It should be noted that the GIPA Act does not affect the operation of the State Records Act 1998[6]

- steps taken by the office to reasonably attempt to locate information.

The Office is not required to undertake any search for information that would require an unreasonable and substantial diversion of resources. Further information on unreasonable and substantial diversion of resources can be found below at section 5 of this Guideline.

Additional information about unreasonable and substantial diversion of resources can be found in the IPC’s Fact Sheet – Unreasonable and substantial diversion of agency resources.

Where should the Minister’s Office conduct its searches?

All possible locations where the information may be located should be searched. This can include the following:

- Records management systems

- Case management systems

- Electronic records saved on computers and electronic devices including laptops, iPads, agency phones. Electronic searches include searches of email accounts

- Hard copy files, including hand-written notes in notebooks

- Records stored offsite or in archives.

Any search should have particular regard to the terms of the access application. For example, if an application requests access to messages, such as SMS or WhatsApp, it would be insufficient to only limit the searches conducted to the electronic email records of the Minister’s Office.

Searches of an electronic back up system

It should be noted that a Minister’s Office is not required to search for information in records held by the Office in an electronic backup system unless a record containing the information has been lost to the Office as a result of having been destroyed, transferred or otherwise dealt with, in contravention of the State Records Act 1998 or contrary to the Office’s established record management procedures.

Keeping records of searches conducted

Search officers should keep a concise account of the steps taken to locate information. It is not enough for the decision maker to simply assert that reasonable searches have been conducted. The office will need to demonstrate that reasonable searches were conducted with reference to the steps taken by the Office. The IPC considers that it is best practice for the search officers to document the following information when undertaking their searches:

- Details of searches conducted

- Search terms used

- Systems searches (electronic databases)

- Any information identified

- Time taken to undertake the search for information

- Other relevant information that might assist the search process for example, information regarding the agency’s record keeping systems and practices

- Outcomes of searches conducted.

Search officers should document the above information even in circumstances where no information is located following the conduct of searches. It might be helpful to develop a form or certification template to assist search officers in documenting their searches which can then inform the decision makers decision. The IPC considers that decision makers should require a positive act by those tasked with undertaking searches and a default position of no response is insufficient.

This is because under section 97 of the GIPA Act, the Office has the onus to justify its decision at review. This means, demonstrating that a reasonable search for all information was conducted in the circumstances. Additionally, search efforts and other functions may inform a decision to impose a processing fee and resultant notice.[7]

The Department of Premier and Cabinet may also provide assistance to Ministers’ Offices that may be useful.

Case studies about what constitutes reasonable searches:

The Appeal Panel in Robinson v Commissioner of Police (NSW) [2014] NSWCATAP 73 discusses that the focus of the question as to whether section 53 of the GIPA Act has been satisfied is to look at the administrative steps taken by the agency’s search officers. The Appeal Panel stated at [33]:

The focus of this enquiry required by s 53 is the administrative steps taken by the agency's search officers. The officers can give a concise account of the steps taken, but that account cannot go so far as to simply assert that what was done (undescribed) was reasonable.

Additionally, in Mizzi v Commissioner of Police (NSW) [2013] NSWADT 150 the Tribunal provides that the question of what constitutes a reasonable search will vary with the circumstances. The Tribunal considered that the key factors in this assessment include:

… the clarity of the request, the way the agency's recordkeeping system is organised and the ability to retrieve any documents that are the subject of the request, by reference to the identifiers supplied by the applicant or those that can be inferred reasonably by the agency from any other information supplied by the applicant.

In line with Robinson and Mizzi, the IPC considers it is good practice to include certain information about the search process in the notice of decision. Further guidance is discussed below at ‘What to include in the notice of decision if information is not held’

It is important to note that in conducting searches, it is not the responsibility of the search officer to determine whether information responsive to searches does in fact fall within the scope of an access application or whether the information should or should not be released. The search officers must provide the decision maker with all information located and responsive to their searches. In providing their search response, the searching officer may provide any information on the public interest factors they identify as relevant for consideration by the decision maker.

Ultimately, it is a matter for the decision maker to review all information held responsive to the searches and apply the public interest test to the information as well as consider any other relevant provisions of the GIPA Act as appropriate (please see section 7 of this Guideline for more information about the application of the public interest test).

What happens if no information is found?

If the decision maker decides under section 58(1)(b) of the GIPA Act that information responsive to the application is not held, this is a reviewable decision under section 80(e) of the GIPA Act.

The applicant is entitled to seek a review of the decision by NCAT, including an option to seek external review first by the Information Commissioner. The Office must be able to justify its decision at review in order to discharge the onus at section 97(1) of the GIPA Act (review by the Information Commissioner) and section 105(1) (review by NCAT).

If the Information Commissioner conducts an external review on application by the applicant, the Minister’s Office will be required to provide the Information Commissioner with information to demonstrate that reasonable searches were conducted. This will form the basis for the Information Commissioner’s consideration of whether the decision that no information is held is justified and any such recommendations that may be appropriate in the circumstances. If the applicant seeks review by NCAT, this information will also likely form the basis of the Tribunal’s consideration of the matter.

Further information about an Applicant’s review rights is set out below at section 8 of this Guideline.

What to include in the notice of decision if information is not held

The Information Commissioner’s Fact Sheet – Reasonable searches under the GIPA Act explains best practice for a notice of decision is to include the following information about the searches conducted:

- An explanation of what the office understands the applicant’s request to be

- How the agency’s recordkeeping system is organised

- How information is retrieved from the recordkeeping system

- If the system is electronic, the search terms used by the office to identify information relevant to the request

- If the system is paper based, how the information is stored and how the office was able to ascertain what information was relevant to the applicant’s request

- The steps taken by the agency to retrieve any documents that are subject to the request.

5. Unreasonable and substantial diversion of resources

Under section 60(1)(a) of the GIPA Act a Minister’s Office may refuse to deal with an access application if dealing with the application would require an unreasonable and substantial diversion of the Office’s resources.

In deciding whether dealing with an application would require an unreasonable and substantial diversion of resources, the Office may take into account other factors or considerations that would assist to inform its decision. For example, the Office may consider 2 or more applications as one application if they are related (section 60(3)). Further, section 60(3A) of the GIPA Act provides that the following considerations may be taken into account:

- The estimated volume of information involved in the request,

- The agency’s size and resources,

- The decision period under section 57 (i.e. the standard 20 working day decision period which can be extended for consultation and other reasons)

Importantly, section 60(3B) states that any consideration under subsection (3A), must on balance, outweigh:

- the general public interest in favour of the disclosure of government information, and

- the demonstrable importance of the information to the applicant, including whether the information—

- (i) is personal information that relates to the applicant, or

- (ii) could assist the applicant in exercising any rights under any Act or law.

The Office is not limited to the above factors when making its decision and further guidance on other factors that may be relevant when determining what constitutes an unreasonable and substantial diversion of resources can be found in Cianfrano v Director General, Premier’s Department [2006] NSWADT 137 (Cianfrano), including:

- The demonstrable importance of the document or documents to the applicant, as a factor in determining what in the particular case is a reasonable time and reasonable effort;

- Whether the request is a reasonably manageable one giving due, but not conclusive regard to the size of the agency and the extent of its resources usually available for dealing with GIPA applications

- The reasonableness or otherwise of the agency’s initial assessment and whether the applicant has taken a co-operative approach in redrawing the boundaries of the application.

It is notable that these factors are not an exhaustive list of possible considerations.

Before the Office makes a decision to refuse to deal with an application because of an unreasonable and substantial diversion of resources, the Office is required to give an Applicant a reasonable opportunity to amend the application. The period within which the application is required to be decided stops running while the applicant is being given an opportunity to amend the application.[8]

The Office is also required to provide an Applicant with reasonable advice and assistance with regard to the amending and/or narrowing of the scope to assist with the facilitation of access to the information being sought.[9]

Case study: Loussikian v University of Sydney [2018] NSWCATAD 140 (Loussikian)

In the matter of Loussikian the Tribunal accepted the estimated processing time provided by the Respondent agency as the Respondent was able to demonstrate that a preliminary search for the information revealed that more than 674 emails fell within the applicant’s request. The Respondent’s evidence of processing time was further supported by a sample consideration of the first 25 identified emails and estimated that to process 674 emails would require at least 139 working hours. The Tribunal accepted that the sample demonstrated a significant amount of consultation would be required by the Agency which would result in further resource application. Additionally, the Tribunal accepted evidence that the Agency had already expended considerable resources in dealing with the application (37 hours). Having accepted the evidence and being satisfied on the facts the Tribunal noted that an agency is not required to provide a more accurate estimate of processing time as it would necessarily require an agency to undertake a broader trial. The Tribunal found that the Agency had taken reasonable steps to form an estimate of the processing time that would be required.

Loussikian sets a standard for agencies when demonstrating the steps it took to inform itself of questions of fact such as:

- estimate of processing time

- volume of information relevant to an applicant’s request.

As stated above, sections 97(1) and 105(1) of the GIPA Act place an onus on the Minister’s Office to justify its decision when the decision is reviewed by the Information Commissioner and NCAT respectively. In circumstances where the Office may make a decision to refuse to deal with an application due to an unreasonable and substantial diversion of resources, it is good practice for the Office to first consider whether it has met the requirements of section 60(3A) and 60(3B) and ensure it provides enough information in its notice of decision to meet the standard set out in Loussikian.

6. Fees and charges

A formal access application made under the GIPA Act requires a $30 application fee to be payable by the applicant when lodging the application. The Minister’s Office can also impose a charge for processing the application of $30 per hour. The $30 application fee counts towards the first hour of processing.

The application fee may be waived, reduced or refunded in any case where the Minister’s Office deems appropriate depending on the applicant’s circumstances and in accordance with Section 51(A) and Section 127 of the GIPA Act. In circumstances where the application is received by the Minister’s Office, but the information is held by another agency the application can be transferred to that agency however the application fee paid remains with the Minister’s Office.

Advance Deposit

Under section 68(1) of the GIPA Act, the Minister’s Office may request the applicant to pay an advance deposit of the estimated processing charge. Section 64(2) prescribes the activities for which processing charges may be charged.

The notice to the applicant requiring an advance deposit must include the following in accordance with section 68(3) of the GIPA Act:

- include a statement of the processing charges for work already undertaken by the agency in dealing with the application, and

- include a statement of the estimated processing charges for work expected to be required to be undertaken by the agency in dealing with the application, and

- specify a date by which the advance deposit must be paid (being a date at least 20 working days after the date the notice is given), and

- include a statement that if the advance deposit is not paid by the due date the agency may refuse to deal further with the application and that this will result in any application fee and advance deposit already paid being forfeited.

Under section 68(2) of the GIPA Act the period within which the application is required to be decided stops running from when the notice to require an advance deposit is issued to the applicant until payment of the advance deposit is received by the Minister’s Office. Section 57(5) requires the Office to issue a notice indicating the date on which the extended decision period will end.

Discount

An applicant may apply for a 50 per cent reduction in processing charges on the grounds of financial hardship under Section 65 of the GIPA Act. Under clause 10 of the GIPA Regulation, financial hardship includes consideration of the applicant’s evidence, where relevant, that he or she is:

- the holder of a Pensioner Concession card issued by the Commonwealth that is in force;

- a full-time student;

- a non-profit organisation, including a person applying for or on behalf of a non-profit organisation.

An applicant may also apply for a 50 per cent reduction in processing charges on the grounds that the information applied for is of ‘special benefit to the public generally’.

Case study: Shoebridge v Forestry Corporation of NSW [2016] NSWCATAD 93

In the matter of Shoebridge, the Tribunal considered whether information could be considered to be of special public benefit for the purposes of a reduction in processing charges under section 66 of the GIPA Act. The information applied for in Shoebridge was found to be of special benefit to the public generally because it:

- related to issues of public significance

- allowed the public to form its own views about whether proper records were kept

- when provided to a Member of Parliament would allow questions to be asked of Ministers and agencies both inside and outside Parliament and/or

- would allow persons who reside in locations adjacent to a project to make submissions or ask questions.

Further, the Tribunal found at [23] that the benefit to the public is to be different from what is ordinary or usual to the general public. The Tribunal states:

In summary, therefore, a decision-maker must decide whether he or she is satisfied that there is a benefit different from what is ordinary or usual to the general public, and thus not merely the private interests of the applicant alone

For guidance, the significance of the information itself and the issues it may inform should be considered in coming to a decision regarding the question of special public benefit. The Tribunal considered the definition of ‘special’ as defined in the Macquarie Dictionary and states at [22]:

As to ‘special’, the Macquarie Dictionary gives a number of definitions of ‘special’. Two are potentially relevant: “distinguished or different from what is ordinary or usual”, or “extraordinary, exceptional, exceptional in amount or degree”…

More information on discounting charges can be found in the Information Commissioner’s Guideline 2 – Discounting Charges.

7. Refuse to provide access to information

Under section 61 of the GIPA Act, the office must ensure that its notice of decision to refuse to provide access to information includes:

- the agency’s reasons for its decision,

- the findings on any material questions of fact underlying those reasons, together with a reference to the sources of information on which those findings are based,

- the general nature and the format of the records held by the agency that contain the information concerned.

Information to which there is a conclusive presumption of an overriding public interest against disclosure

The Office should first identify whether there is a conclusive presumption of an overriding public interest against disclosure of the information requested (see Schedule 1). If information falls within the scope of one of the clauses in Schedule 1 to the GIPA Act, then it is conclusively presumed that it is not in the public interest to release the information. This means that the Office is not required to identify public interest considerations in favour of disclosure or determine the balance of public interest considerations in accordance with section 13 of the GIPA Act before refusing access to the information. However, the application of Schedule 1 may require the Office to be satisfied that the facts support the application of a conclusive presumption that it is not in the public interest to release the information.

These considerations require essential elements be met for their application to the information. Information commonly dealt with by Ministers’ Offices is information considered cabinet-in-confidence. The IPC has developed a number of resources to assist agencies when dealing with cabinet information, including the Information Commissioner’s Guideline 9 – Cabinet Information which includes a checklist which assists in the identification of cabinet information.

Applying the Public Interest Test

If the information does not fall into the scope of one of the clauses in Schedule 1 of the GIPA Act, before making a decision to refuse to provide access to the information, the Office must undertake a public interest test in accordance with section 13 of the GIPA Act to satisfy itself that there is an OPIAD. Section 13 provides:

There is an overriding public interest against disclosure of government information for the purposes of this Act if (and only if) there are public interest considerations against disclosure and, on balance, those considerations outweigh the public interest considerations in favour of disclosure.

The IPC resource Fact Sheet – What is the public interest test? provides further guidance on how to conduct the public interest test. The core elements of the public interest test include:

- Identifying the relevant public interest considerations in favour of disclosure

- Identifying the relevant public interest considerations against disclosure.

A Minister’s Office must determine the weight of the public interest considerations in favour of and against disclosure and come to a conclusion about whether the factors favouring non-disclosure are strong enough to outweigh the factors in favour of disclosure (taking into account the presumption in favour of disclosure – see below). It is important to note that the public interest test must be undertaken on the pieces of information within a record and not on a document as a whole.

If the Office finds that there is an OPIAD to only some of the information within a record, the Office may partially release the record by making redactions to the information to which it considers there is an OPIAD which in turn will allow the provision of access to the other information to which there is no OPIAD.[10]

Case study: Taylor v Office of Destination NSW [2018] NSWCATAD 195

In order to justify its reliance on a public interest consideration against disclosure, the Agency must identify the relevant information in each record and apply the public interest test to the actual information. This approach is consistent with the matter of Taylor v Destination NSW [2018] 195 (Taylor) where the Tribunal held that an agency is required to consider the public interest consideration against disclosure in relation to the relevant information and not to categories of information. The Tribunal stated [at 18-19]:

In the internal review decision of 15 September 2016, the Respondent applied the public interest test to each of the six categories of documents identified as numbered items in the Applicant’s access application, without specific reference to the documents containing the information caught by the requests in the access application. As noted in the Tribunal’s reasons for decision in Taylor, this was a fundamentally flawed approach because the public interest test in the GIPA Act requires examination of the government information, to apply the public interest test to that information, and not to ‘classes’ or ‘categories’ of documents.

The Respondent has sought to rectify this approach in the reviewable decision by referring, by number, to each of the documents caught by each category. However, the Respondent has not identified for the Tribunal the specific information in each document which it says should be withheld on the basis of its concerns regarding disclosure, and that which can be released. The Respondent has instead applied the public interest test to the category of document, rather than identifying the relevant information in each document and applying the public interest test to the actual information. This approach attempts to short-cut the balancing exercise required by correct application of the GIPA Act.

Therefore, it is important that the Office identifies the information within each record of concern and conduct the public interest test on the specific information within the record.

Steps to consider when undertaking the public interest test

- Start from a position that there is a general public interest in favour of disclosing government information (Section 12(1))

- Identify further considerations in favour of disclosure that are tailored to the individual request. While not exhaustive, Section 12(2) provides the following examples of public interest considerations in favour:

- Disclosure of the information could reasonably be expected to promote open discussion of public affairs, enhance Government accountability or contribute to positive and informed debate on issues of public importance.

- Disclosure of the information could reasonably be expected to inform the public about the operations of agencies and, in particular, their policies and practices for dealing with members of the public.

- Disclosure of the information could reasonably be expected to ensure effective oversight of the expenditure of public funds.

- The information is personal information of the person to whom it is to be disclosed.

- Disclosure of the information could reasonably be expected to reveal or substantiate that an agency (or a member of an agency) has engaged in misconduct or negligent, improper or unlawful conduct.

- Identify the considerations against disclosure (section 14). The table in this section details the prescribed considerations against disclosure that the office may consider relevant to the information subject of the GIPA request. The Minister’s Office must be able to justify its reliance on any of the considerations against disclosure by applying the considerations to the information within the record and making findings on material questions of fact.

- Consider whether there is a necessity to consult with third parties. Sections 54 and 54A outline circumstances which may trigger the need to consult, generally this is where the information contains details about other individuals, businesses or agencies. If consultation is required, the decision period can be extended by up to 10 working days with a maximum of 15 working days (see section 57(2)). Further information on timeframes can be found in the IPC fact sheet Fact Sheet – Timeframes and extensions for deciding access applications under the GIPA Act.

The IPC has a comprehensive guideline which provides further guidance on consultation. Information Access Guideline 5 – Consultation on public interest considerations under section 54 and Section 54A of the GIPA Act. It is best practice to maintain clear records of consultation. It is important to note that an objection received by a third party that is consulted is not of itself determinative that the information cannot be released, rather it is a factor to be taken into account in the balancing of the public interest test. Decision makers are reminded that review rights are also attached to decisions made to provide access to information relating to a third party and should therefore be familiar with those review rights when finalising its decision.

- Weigh those considerations in favour against those against disclosure. When balanced, if the weight of those considerations against disclosure outweighs those in favour this may lead to a decision that there is an overriding public interest against disclosure. The IPC has developed a template – Notice of Decision (Word) to assist agencies in addressing the essential elements.

8. Rights of review

Formal and informal rights

If the Minister’s Office makes a reviewable decision under section 80 of the GIPA Act, the notice of decision should inform the applicant of their rights of review. An applicant has three rights of review:

- right to seek an internal review of the office’s decision,

- right to seek external review by the Information Commission

- right to seek external review by the NSW Civil and Administrative Tribunal (NCAT).

The office’s notice of decision should advise the applicant of their review options.

Internal review

Note: Under section 82(2) of the GIPA Act internal review is not available to Applicants if the decision of an access application was made by a Minister or a member of the Minister’s personal staff.

The Applicant has 20 working days from the date the decision is given by the Minister’s Office to request for an internal review.

The Application for internal review can be made in writing to the Minister’s Office.

The Applicant is required to pay a $40 application fee for internal review unless:

- the Minister’s Office agrees to waive or reduce the fee; or

- the Applicant requesting for internal review is of a decision to refuse to deal with an access application because the Minister’s Office did not decide the access application within time in which case no fee is payable; or

- the internal review was recommended by the Information Commissioner.

The Minister’s Office should acknowledge receipt of the internal review application in writing as soon as practicable preferably within five working days after the application is received.

The internal review application must be decided, and a notice of decision provided to the applicant within 15 working days after it is received. The decision period can be extended and up to 10 working days for either or both of the following reasons:

- Consultation with another party who were previously not consulted when the Minister’s Office made its original decision.

- The Minister’s Office reasonably believes that more than one person is entitled to an internal review for any reviewable decision for the same access application.

The Minister’s Office must provide the Applicant before the internal review period ends notice to advise of new due date on which the extended internal review period will end.

Additional information about internal review rights is available in the IPC Fact Sheet – Internal Reviews under the GIPA Act.

External review by the Information Commissioner

If an Applicant is dissatisfied with a formal decision made by the Minister’s Office, the Applicant is able to request for an external review by the Information Commissioner. The Applicant has 40 working days from the date the decision is given to the Applicant to request for an external review by the Information Commissioner. A working day is defined as any day that is not a Saturday, a Sunday or a public holiday or any day during the period declared by the Premier as the Christmas closedown period.

An application for external review can be made by the person applying for the government information and a person who objects to the release of that information.

The Information Commissioner has no discretion to accept an application made out of time.

Additional information about external review rights is available in the IPC Fact Sheet – External review by the Information Commissioner.

External review by the NSW Civil and Administrative Tribunal (NCAT)

The Applicant is able to request an external review by the NCAT if the Applicant disagrees with any of the decisions made by the Minister’s Office or Information Commissioner. The Applicant has 40 working days from being given the decision to apply to NCAT for review.

If the Applicant has applied for review by the Information Commissioner, the Applicant has 20 working days from being notified of the Information Commission’s review outcome to apply to NCAT.